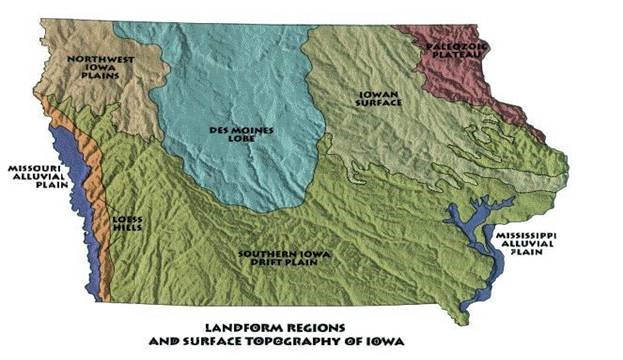

We Iowans hear all the time about how our state is flat from outsiders. As natives, that doesn’t seem entirely fair. While about a third of the state is very flat, the rest of it—isn’t. In fact, there are seven different landforms in our state, and each one has a different story.

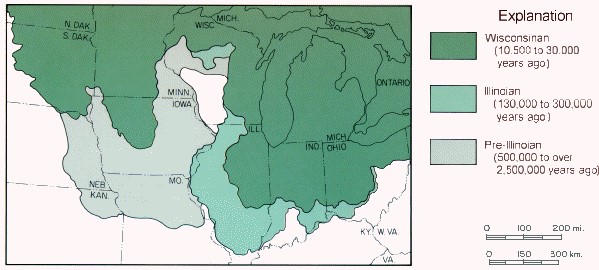

Iowa’s primary soil parent material is glacial till. That just means that our landforms are largely due to the glaciers that the state has seen over the past couple million years. Naturally, there are exceptions, but let’s start from the beginning (or at least two million years ago), shall we?

From between 500,000 and 2,500,000 years ago (pre-Illinoisan period), a huge glacier moseyed its way through the Midwest. These glaciers moved at a relatively normal pace, about half a mile per year. Because of the slow speed, it created some lovely, rolling hills as it pushed across the state.

In addition to the slow pace of the glacier, erosion naturally happens over time. Therefore, the slopes in the Southern Iowa Drift Plain have become more pronounced by wind and rain. Streams cut through the original hills for tens of thousands of years, and made our southern landscapes hillier. Though today we do our best to slow erosion and protect our soils, some erosion is natural and simply a fact of geology.

The Loess Hills are a wonderful and unique point of Iowa pride. Loess is a wind-blown soil type, and actually influenced more than just the Loess Hills. The sediment was taken from the Missouri Riverbed, and was blown east. In soil, there are three main particle sizes: sand (largest), silt, and clay (smallest). So when wind began blowing sediment out from the riverbed, the smallest particles (clay) blew to the eastern part of the state, silt blew to the western part of the state, and the sand stayed primarily in the riverbed.

The Loess you see in the Loess Hills can look yellow, or light colored. This soil behaves differently than other kinds of soils, and can create large, rolling hills. This soil type, one of the most fertile on Earth, can only be found in two places in the world; here and in China. However, because of its interesting qualities, loess can be easily erodible. Farmers in this area can still benefit from the fertility of the soil, but they may farm on a contour (around the hill), leave grass waterways, or terrace their fields, to help conserve their land for years to come.

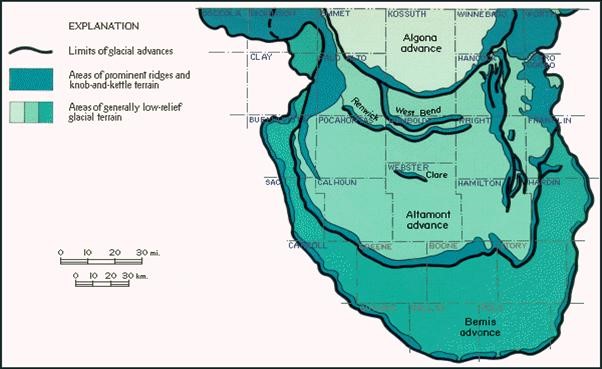

About 10,500 years ago, the newest glaciation swept through Iowa. This glaciation, known as the Wisconsinan Glaciation, scooted its way down the north-central part of the state at lightning speeds – two miles per year! If you look at the picture above, you can see it looks kind of like a thumb. That formation is called the Des Moines Lobe of the Laurentide ice sheet, or just “the lobe.”

This is important for a lot of reasons. When the Wisconsinan Glaciation took place, it brought down beautiful, rich, black sediment, perfect for growing corn and soybeans when paired with our climate. The glacier also leveled off the land, leaving it flat, and easy to till.

In fact, as you’re driving through our capital city, you can see exactly where that glacier stopped. Its terminal moraine, or the end point (a hill of remaining glacial till sediment), is the hill our capitol building was built on.

The glacier left some other marks on our landscape, as well. It advanced and receded a number of times, leaving pockets of sand, silt, rocks, and “kettleholes” as it went. The map below shows some of those advances, and where to look for other landforms. This glaciation also affected the Northwest Iowa Plains and the Iowan Surface, whose hills could be described as more “wavy” than the steep hills we see to the south.

Our last two landscapes are the oldest and the youngest.

The Paleozoic Plateau, though glaciated, has little glacial till, and is still largely rocky. When you visit, you might notice forested areas, large rock formations, and streams. These formations can be anywhere from 300 million to 550 million years old. This part of the state is home to many of our dairy operations!

Alluvial plains, the youngest landform, are something like an antique flood plain. These formations were created from deposited sediment from running water. In terms of soil parent material, this is called alluvium. It can be extremely variable, depending on what type of sediment the river depositing it was carrying. Though these areas can become flooded in wet years, farmers take advantage of the level terrain by planting row crops.

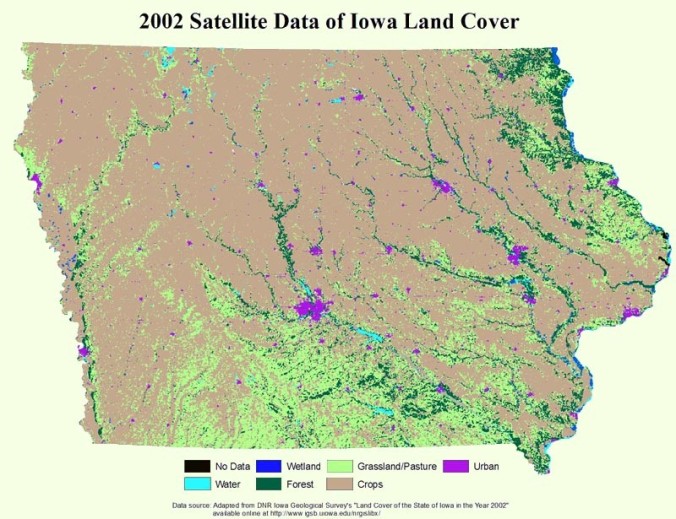

All of these various landforms impact the way farmers use their land. For instance, farmers on the lobe may plant acre after acre of corn and soybeans on beautiful, flat soils, but towards the south, farmers leave more acres as grassland, hay, or pasture for livestock.

Though Iowa is unified through agriculture, our geography dictates some of our roles within it. I encourage you to take a longer look at the countryside the next time you drive through the state. Try to analyze what you see and why you might see it. If you meet a farmer or two, ask them about how their land’s characteristics impacts how they use it. Ask them about how they use hillsides and forested land, how they manage creeks and rivers, and how they mold their practices to the landscape.

Just remember – Iowa isn’t all flat.

-Chrissy

Pingback: Why do they do that? – Terraces and Tile Lines | Iowa Agriculture Literacy

This article is so informative, friendly, and highly readable. Not at all what I expected from an ag-literacy site! Thanks so much for such an entertaining read!

LikeLike

Pingback: You’re attending the 2021 National Agriculture in the Classroom conference. Now what? | Iowa Agriculture Literacy

Pingback: You’re attending the 2021 National Agriculture in the Classroom conference. Now what? – Aerospace

Pingback: Asad’s Droppings are Full of Iowa Mudstone | sara annon